The biologists at the fisheries office in Nome, Alaska, gave me a tip: There were still late-run sockeye 40 miles inland on the Nome-Teller Road at the outlet to aptly named Salmon Lake. The drive was one of those peak experiences you never forget.

At that latitude, the sun shines at a sharp angle all day, which makes the rust-and-umber foliage of the landscape luminous. And as I drove, I viewed it through the cracked-in-three-places windshield of an old mud-encased Jeep while listening to my new favorite radio station, KNOM, for as long as the signal held. Because Alaska is so big, the region-by-region weather forecast takes almost 10 minutes. Then comes the salmon report: Chums are way up the Yukon River and in bigger-than-usual numbers. Another preoccupation is the current prices for gold and silver. Then hunting: Moose season in subarea RM 840 is closing at 11:59 a.m. because hunters have already taken 23 bulls. And messages from family members to loved ones to get in touch with them, and from others to their families saying they’re OK, and they’ll find a job soon and be fine. Quintessential Alaska.

Today, Nome has fewer than 4,000 residents.

Today, Nome has fewer than 4,000 residents.

It was September, and Nome was busy being a remote Alaskan outpost with its usual fixation on gold, but with minimal tourist interest. That comes in March, when the Iditarod mushers end their 900-mile dash from Anchorage at the finish line in downtown Nome, just one block from the Bering Sea. I have no love for gold, but I am sweet on silver salmon, and scanty intelligence suggested they make an uncelebrated late-summer run there. I found myself in Nome, alone and ready to prospect.

Nome’s Fishing Culture

Today, Nome has fewer than 4,000 residents, mostly native Inuits, but during the height of Gold Rush mania at the turn of the 20th century it was the most populous city in Alaska. Gold nuggets were discovered in a nearby creek in 1898, followed by gold dust on the beach sands. One year later, Nome held 10,000 people, and in June 1900, an average of 1,000 newcomers were arriving by steamship each day, a “tent city” ran along the beaches for 30 miles, and lucky strikers could spend their wealth at more than 60 saloons. Like all booms, it went bust. Just 10 years later, the richest sites were tapped out, and Nome’s colorful phase of history was over.

A remote outpost, Nome was Alaska’s most populous city at the turn of the 20th century, thanks to the discovery of gold.

A remote outpost, Nome was Alaska’s most populous city at the turn of the 20th century, thanks to the discovery of gold.

My host for lodging, Igor Kislitsyn, picked me up at the airstrip. I liked him immediately; a Russian born near Lake Baikal, he had the casual confidence of someone who has taught skydiving, worked as a factory lawyer, and dredged underwater for gold, among other precarious pathways to making a living. Though we passed a giant replica of a gold pan, my first impression of Nome was not of gold booms or mineral riches — the houses seemed downright dilapidated. But it occurred to me that villages in Greenland, Labrador or Siberia wouldn’t look much different. Instead of a lawn, you have eight wooden pallets, two busted ATVs and an old Chevy engine, but so what — it’s a harsh existence anywhere around the Arctic Circle. Expediency rules; those who try to make their front yards more showy use planters made from rusted gold-dredge buckets.

My plan was to fish many of the 20 or so rivers crossed by the three dirt roads that radiate 75 miles out of town and into the wild. Because of some confusion, the Jeep I thought I had reserved from Igor was for the moment being rented to another guest. Dr. Lynn Barber generously shared the vehicle, dropping me off at creeks while she went off birding. Lynn is one serious birder. She once had a national “big year” of viewing 723 kinds of birds and was working on an Alaskan big year. We talked birds as we drove through the tundra, which meant that she did most of the talking.

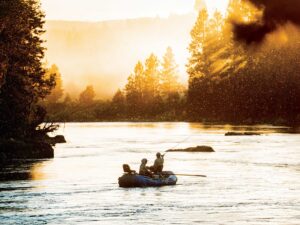

Waldman targeted whitefish, grayling, Dolly Varden and salmon in a variety of creeks and rivers.

Waldman targeted whitefish, grayling, Dolly Varden and salmon in a variety of creeks and rivers.

Journey Through Nome’s Scenic Routes

On the first day, Lynn left me at a fine-looking stretch of the Solomon River. I worked it for two hours, but the only fish I saw were dead pink salmon. I soon learned that in any of Nome’s rivers you are never more than 10 feet from a pink carcass, and there is a good chance you are standing on one. This lack of live fish in what was gorgeous water was discouraging — as were the many bear footprints in the sand — and made me think that maybe it was too late in the season. Farther upriver, below a high overlook, I spotted an unreachable school of about 40 silvers, glowing crimson after days removed from the sea. At a bend upstream from there, I discovered a long trough I called the “diversity hole,” where I landed several nice Dolly Varden, my first ever chum salmon, an awful-looking pink — the only one still alive of the thousands I saw that week — and what I had come to Alaska for: a silver.

My quick success in Nome was a karmic contrast to the beginning of the trip. After leaving New York and spending the night on an airport bench in Seattle, I learned that my 6 a.m. flight to Anchorage had been canceled. Remarkably, Alaska Airlines said it didn’t have enough crew to fly. That meant I would miss my connection and lose 24 hours in Nome. To salvage part of the day, I made it to Anchorage on the next flight and went exploring.

I was drawn to Ship Creek, the famous but sad downtown stream that is overstocked with all kinds of salmon, even kings. When the fish are running, it is shoulder-to-shoulder combat fishing. I saw only two beat-up pinks and a few guys practicing illegal, not to mention nonsensical, catch-and-release snagging, with stacked shipping containers forming an industrial backdrop.

On my second day in Nome, Lynn dropped me off at a small river called Cripple Creek, where I enjoyed a willing pod of spawning Dollies in skinny water. Nome Dollies are creatures of exquisite beauty, sea-run fish that have small heads, powerful bodies and vibrant spawning colors, along with plucky attitudes. That evening, Lynn left for Anchorage, and I claimed the Jeep to explore on my own, stopping first at the Nome Visitor Center. Two lost souls, emigres from the Lower 48, were hanging out there, one of whom unexpectedly asked, “Has anyone ever told you look like Ulysses S. Grant?” I said no, but he took out a $50 bill and compared me to Grant’s image. Oddly, he looked more like the 18th U.S. president than I did.

I fled that weirdness and went to where the Nome River meets the sea. On the other side of the channel, I sighted the only other fly rodder I saw all week. He was my hero, a determined paraplegic fishing solo. The young man drove his truck to a point on the beach, dropped into a wheelchair, rolled it over the sand and cast from his sitting position. When he wanted to move, he broke down the rod into two pieces, held it in his mouth and set up again. When finished, he reversed the process. But his truck got stuck in deep sand. I don’t know how he managed, but he somehow rocked the vehicle back and forth and extricated it.

A sockeye in hand.

A sockeye in hand.

Historical Context: Nome’s Gold Rush Legacy

The next day, Igor asked to come along with me. I reviewed his fishing equipment: typical Alaska “football bat” for meat-production snagging. But I thought enough of Igor to loan him a fly rod and to devote the day to turning him into a fly caster. After a Fly-Fishing 101 session, we stalked spawning char at Cripple Creek. Igor’s casting wasn’t pretty, but he was an excellent student and noticed the subtleties of presenting a fly. He eventually landed a Dolly and later shopped online for a 6-weight outfit.

In return, Igor taught me how to pan for gold, leaving me to swash gravel while he fished. This was fun for maybe 10 minutes, then became hard work, with no gilt to show for the effort. Today’s techniques to search for gold in Nome are more sophisticated — mostly dredging offshore for dust, not river-panning for nuggets. Jury-rigged dredge boats are everywhere, working the coastline, docked in marinas, parked in driveways. When you dredge for gold, one of the two-member crew goes to the bottom in a suit that has water pumped into it from the boat’s engine, a difficult-to-regulate process that can cook or freeze the person.

One day, Igor noticed a crack in the wall above a doorway in his home, then spent hours jacking the corners of the house up and down to compensate for the no-longer-permanent permafrost its foundation sits upon. That evening, I asked him to help me locate the musk oxen herd that wanders the edge of town. After a good deal of searching, we surprised them in a hollow and drew close to these striking examples of Pleistocene megafauna. Igor follows them in the spring when they are shedding to collect their underhair from bushes. Used in high-end clothing, this qiviut nets him more than $30 an ounce.

A nice, fly-caught coho (silver) salmon.

A nice, fly-caught coho (silver) salmon.

My visit with the regional fish biologists in town provided some solid information on Nome’s rivers. The sheer health of these little systems is astounding. No dams, no pollution. Period. The Nome River is no bigger than an Eastern trout stream like the Beaverkill, yet the biologists had just counted more than 700,000 pinks in it. And it was an odd year; on even years they run more than a million in the Nome. (Pink salmon have alternating odd- and even-year seasonal runs.) Silver numbers in this little flow vary between 5,000 and 10,000. And every other river is similar in its modest size and astonishing productivity, the spawning of the migratory salmon followed by their compulsory dying, thereby delivering the richness of the sea with a nutrient injection to what would otherwise be nearly barren waters.

On the day I arrived at Salmon Lake, the outlet had a few dozen sockeye cavorting, some with their backs out of the water. I landed one on my third cast, but sockeye can be tough, and the next one came a long while later. I also talked fish with a native hunter out for moose. When I asked about whitefish, he told me that the pool at the bridge on the Kuzitrin River 30 miles farther down the road was filled with them. I badly wanted to catch a whitefish, but I wasn’t sure I had enough fuel for the round trip; however, I was certain I didn’t want to spend a night stuck in the car in the wild.

Igor Kislitsyn with fresh silver fillets, the fish atop Waldman’s target list.

Igor Kislitsyn with fresh silver fillets, the fish atop Waldman’s target list.

Luckily, I encountered a native woman who said she had some gas stored at her cabin a few miles away. I followed her to a ramshackle spread ringed by about a dozen old vehicles she’d inherited from her dad; she’d just returned from Abu Dhabi to figure out what to do with it all. It turned out that most of her gas had been stolen, and she said she knew the culprit. I added two gallons to my Jeep’s tank and headed deeper inland.

The pool on the Koutzmarin was, indeed, loaded with whitefish. I waded out on a shore-to-shore gravel bed, the current rippling over a steep dropoff. Hundreds of whitefish were holding in its depths, rising to some prey I couldn’t discern. I went through my fly box — dries, wets, nymphs, egg patterns — but nothing worked, a defeat that still mystifies me. For consolation, on the way back, I stopped at the Pilgrim River, a wide flow with many bars and side channels. One sluiceway had grayling rising, which were fully cooperative, with some running 17 inches. I’m now a big fan of the sailfins, which are warriors and shoot like rockets from the bottom to take dry flies.

On my final day of fishing, I tried for giant grayling on the Niukluk River, the waterway where line-class world records have been taken. This is also deep in the interior, requiring a drive along 10 miles of Safety Sound — a barrier beach lagoon that mariners would tuck into to escape rough seas — passing its many Inuit fishing camps decorated with whale bones before turning inland for another 60 miles and traveling through steadily ascending, lightly inhabited tundra valleys. The temperature plummeted, and at one high pass a freezing wind howled. I finally arrived at a valley with what looked like the Land of Oz in the far distance. It was the Village of Council, which has an official U.S. census population of zero because it is now a seasonal fish camp; during the Gold Rush, 10,000 people lived here.

The author became a big fan of grayling while in Nome, referring to them as “warriors.”

The author became a big fan of grayling while in Nome, referring to them as “warriors.”

Reflections and Insights

Standing on the bank, I could see about 30 homes on the hill across the river, but there is no bridge to Council. To get there requires driving across well more than 100 yards of fast-flowing water. I briefly considered the dash across, but sanity prevailed, and I fished my side of the river. Dead pinks littered the bottom, but there were no grayling in evidence. I made up for it by stopping at two other rivers on the way back to the coast, happily settling for silvers.

I said goodbye to Nome the next morning by driving to the top of a mountain at the edge of town to visit a former “DEW” radar installation — our ears on Russia — from the Cold War. Later, after boarding a plane for Anchorage, the captain announced we couldn’t take off right away. The runway had to be cleared of musk oxen.

Editor’s note: John Waldman, an aquatic conservation biologist with an emphasis on migratory fish and river restoration, and a tenured professor, wrote this story based on a trip to Nome he made several years ago. He reports that little has changed.