We approached the charter boat just as the customers were saying their goodbyes to the captain and mate and dragging their coolers to their trucks. It was about 2 o’clock in the afternoon, and the temperature was in the low 90s.

“We’re hot, we’re grouchy, and we really don’t want to talk,” warned the mate as we introduced ourselves. We shook hands anyway and stood on the finger pier, baking in the July sun for an awkward moment or two before we were finally invited aboard.

This was the third time in five weeks that photographer Michael Cevoli and I had prowled the fishing docks in the port of Galilee, Rhode Island, putting together this photo essay on captains and mates. By now, we had gotten used to the blunt honesty of the men running the charter and party boats out of this rough-hewn fish town. Behind the requisite gruffness, most of these hard-working souls were generous with their time and stories, despite having already logged 10 or more hours on the job with more waiting before they could finally close their eyes on the day.

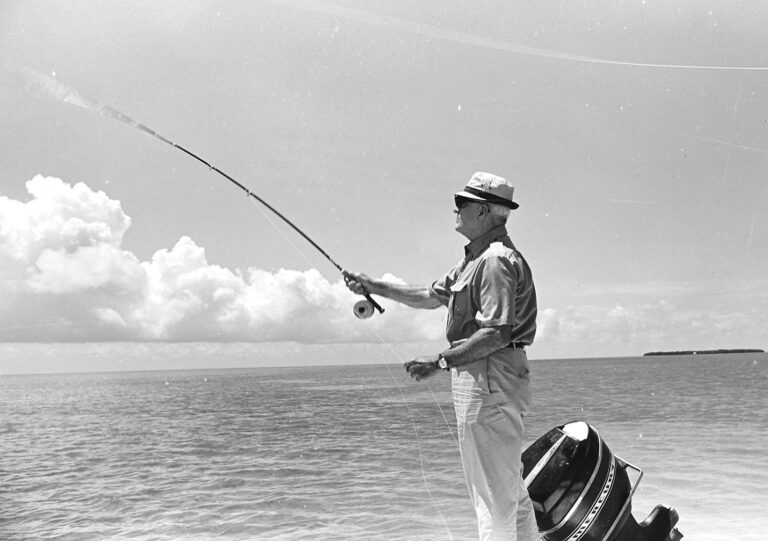

Our goal was to capture a cross-section of the fishermen after they’d spent a long day in the saddle — hot and bothered, sweaty and unvarnished, satisfied or ill-tempered, the mood usually hinging on whether the fish, weather, customers, equipment and lord knows what else happened to be cooperating that day. Like most of us, they typically were in a better mood when they were catching well than on slow days.

We were looking for honest faces and unfiltered talk — portraits of the crusty, the cantankerous, the authentic. Young and old. Wizened and foolish. Ocean poet and monosyllabic deckhand. You can read a lot in a man’s face. Lot of miles, fish, weather — and more.

I interviewed them in their cockpits, wheelhouses and on the docks, wherever we could find a little shade, scribbling notes about their fishing lives, their jobs, their boats, their children, the changes they’ve seen, their dreams and frustrations. As we settled into conversation, the men opened up, and Cevoli burned through digital memory cards.

“I love shooting this way,” says Cevoli, 33, a documentary photographer from Bristol, Rhode Island, whose subjects have ranged from Pennsylvania coal miners and bikers to New England commercial fishermen and tugboat crews. “They’re interacting with the writer rather than the camera, which makes them more relaxed. You can get strong pictures. The photos are honest. Raw.”

We both like proud, feisty underdogs, or what Cevoli calls “low-brow outsider culture.” You certainly can find plenty of that burly, independent spirit here in Point Judith, the section of Narragansett that encompasses Galilee and which the fishermen simply refer to as the “Point.”

What came through clearly after more than a dozen interviews was this: With each passing year, the day-to-day job of these fishermen becomes increasingly difficult and the future less predictable due to rules and regulations, rising costs, uncertainty over fish stocks and other factors.

Despite the frustrations and the pessimistic writing on the wall, they profess that there is nothing they’d rather do than be on the water and fishing. That is the paradox. “I’ve seen the best, and I’m starting to see the worst,” says Capt. Andy Dangelo, 63, who runs the 36-foot Maridee II and has been fishing all his life. “If they can keep the politics out of fisheries management, things would be a lot better. Everything is such a battle these days.”

Loving his work

Despite the challenges, Dangelo, who holds a bachelor’s degree in wildlife biology and an associate’s in marine technology, says he wouldn’t trade his job for another. “I like to watch people catch fish, and I like finding fish, too,” says Dangelo, who holds the state record for a 718-pound mako. “It’s a disease. You have to love it. You’ll never get rich, but I still enjoy it. If you don’t, you’ll go nuts.”

Longtime captain Russ Benn echoes those sentiments.

“I still get a kick out of watching people catch fish and watching new mates come on board,” says Benn, 65, who has been fishing for 47 years and runs the 36-foot charter boat Jeanie B and 80-foot party boat Seven B’s V. “I love what I’m doing. Look out this window,” he says, gesturing from the pilothouse of his Harris 36. “This is the view from my office. Until my arms fall off, this is what I’ll do.”

On most days, Benn is accompanied by Luci-Lou, who is part American bulldog, part beagle and is better known on the docks than some mates. “She’s got a better attitude, too,” Benn says with a smile.

Benn is a respected captain who’s hired more than 100 deckhands during his long tenure in Galilee. He says they become like family. He’s watched them grow, mature, marry and start families. He’s even had second-generation mates sail with him. “We call them fish heads,” he says. “They’re either crazy about fishing or they just have to be on the water.” (The same, of course, is true of Benn.)

And he’s always willing to take a flier on a young person who needs a chance and a job. “Keep them off the drugs. Keep them off the booze,” Benn says. “I’ll pay them something to keep them off the street.”

At 73, Capt. Andy Ambrosia, who’s been fishing since the 1950s, is probably the senior-most member of the tribe. “I love it. I really do,” says the skipper of the 43-foot, Bolger-designed Misty, which he built in 1969. “I’d never want to do anything else.”

He, too, acknowledges the challenges that charter fishermen face today, ticking off a list of complaints, from over-regulation to a proliferation of part-time competition. “This port has changed so much in the last 25 years,” says Ambrosia, who fishes with son Mark.

“It’s very hard to make a living. I’m part of a dying breed.”

80 years too late

He’s not alone.

“I am a living dinosaur,” declares Capt. Richard Chatowsky, who runs the 37-foot diesel-powered Drifter, which he fishes without a mate. “My wife says I was born 80 years too late.”

A full-time second-generation charter captain, Chatowsky also recites a litany of hurdles and changes that make the job not quite what it used to be. But in another breath, he says it’s all worthwhile. “I love it. I do,” says Chatowsky, 48, who fished summers with his father and took his first giant bluefin at age 14. “Where else are you going to get this kind of freedom? You’re your own boss. You make all your own calls. It’s unique in its own way.”

And if he were to win a million-dollar lottery tomorrow, he says, he might leave the charter business in his wake, but he wouldn’t quit fishing. “I’ll never leave the ocean,” he says.

“It takes all kinds to make the Point work,” says deck ape Zach Harvey. “We’ve all been accused of being complainers. But we work hard,” says Harvey, 39, a poet of the Point and frequent contributor to Anglers Journal. “We’re just fish-afflicted.”