Photos and captions by Jeff Dworsky

Father and son tow an empty dory soon to be filled with herring twine.

Father and son tow an empty dory soon to be filled with herring twine.These images depict life in the small fishing village of Stonington, Maine, during a four-year period starting in 1989. You don’t have to look hard to see the bone-weary tiredness of long days on the water. A fisherman holding his head in his hands. Another looking off vacantly, nearly asleep on his feet. Men in flannel, slouching, leaning on a pile of nets, a cigarette stuck to the lower lip of one, pinched between the thumb and index finger of another.

Keeping an eye on an older fella, boarding from the bulkhead.

Keeping an eye on an older fella, boarding from the bulkhead. Securing gear in a blow at Colwell Brothers, a former lobster dealer.

Securing gear in a blow at Colwell Brothers, a former lobster dealer. The photos were taken by Jeff Dworsky, who moved to Stonington when he was 17 and worked for 40 years as a fisherman. Revealing in their honesty and documentary feel, Dworsky’s images capture a bygone era, a way of life in a tight-knit community on the cusp of change. A world before smartphones, Wi-Fi and artificial intelligence. You fished on your wits, skills and experience, with a thin safety net or none at all.

“The analog world,” Dworsky says.

Wallflowers catch up at a dance at Reggie’s Musitorium, a live-music venue.

Wallflowers catch up at a dance at Reggie’s Musitorium, a live-music venue.These Maine fishermen shared the common language of tools and handwork that bridged generations and geography. They fixed or cobbled together boats and gear that were broken, failing or just worn out. They read the water, worked the tides and developed a weather eye. Some could even smell fish. They mastered the mechanical world and the vagaries of the coastal waters as adroitly as millennials navigate the digital sphere with an iPhone.

On a morning when temperatures are around zero, the “boys” have a gam in the office of the Stonington Lobster Co-op, which exists today.

On a morning when temperatures are around zero, the “boys” have a gam in the office of the Stonington Lobster Co-op, which exists today.They looked at the world pragmatically. Fog? “I remember my father telling me it’s the same way out as it is back in,” a Maine lobsterman told me.

The days of yore, when Steve and Edna knit heads for lobster traps.

The days of yore, when Steve and Edna knit heads for lobster traps.The lobster boats pictured here are small, narrow and tender by today’s standards. They were valued for their function above all else; their owners didn’t have the luxury of growing overly sentimental about them. They fished their boats hard, right to the nub.

Child care sometimes included hanging out with dad’s friends on a gusty day.

Child care sometimes included hanging out with dad’s friends on a gusty day.Look closely, and you’ll see artifacts from the old world: a black rotary phone, clothes drying on a line, wooden lobster traps, a steadying sail, wristwatches, a pencil sharpener, a roll-top desk. Those shots that transcend time reveal lives tied to the sea, and a sense of place and community embodied by dozens of small fishing towns from Maine to Alaska.

Jeff Dworsky

Jeff DworskyAbout the Artist

By Krista Karlson

Jeff Dworsky, who took the photos in this story, moved to Stonington, Maine, in 1973 when he was 17 years old. The place was everything his childhood home wasn’t: rural, working-class, gritty. He fit in more than he ever had in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where his mother was a professor at Harvard University.

The views of a father and daughter sitting in the cab of a pickup at the wharf.

The views of a father and daughter sitting in the cab of a pickup at the wharf.At the time, Stonington was a separate world. The single bridge to Deer Isle, where the town is located, didn’t see much traffic. Dworsky, who dropped out of school at 14, was an outsider. But he made friends quickly and gained the trust of many of the town’s roughly 900 residents. They were mostly fishermen, who lobstered, crabbed, scalloped, shrimped and fished for halibut and herring in the cold Atlantic. Fishing had always been the business in Stonington, beginning thousands of years ago with the Abenaki people. The town’s granite quarry boom at the turn of the 20th century came and went, but fishing remained.

Before summer people began buying up the shorefront, fishing families lived as close to the sea as possible.

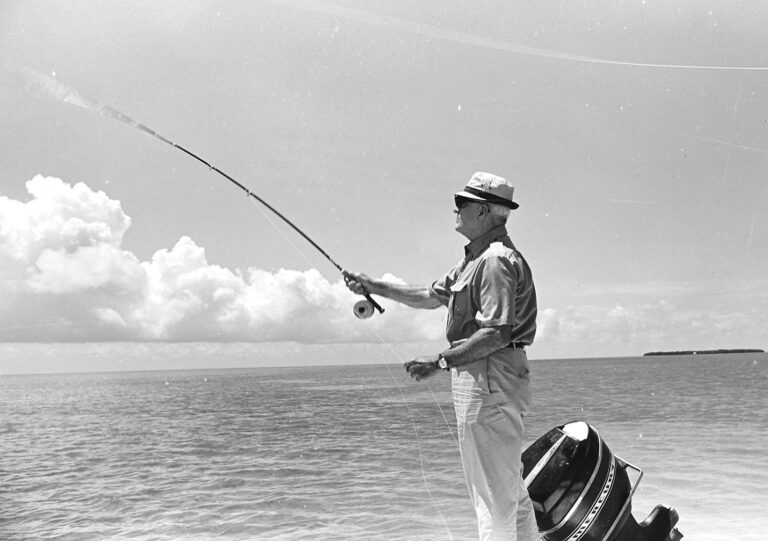

Before summer people began buying up the shorefront, fishing families lived as close to the sea as possible.In 1989, having lived in Stonington for more than a decade, Dworsky picked up his Leica camera loaded with Kodachrome 64 slide film and started photographing through a wide-angle lens the place he held dear. He wanted to document a way of life that he feared was vanishing with the real estate boom of the 1980s, which brought wealthy outsiders to the island. “I saw the Stonington I loved disappearing,” he told me when we met in Belfast, Maine, this past fall.

Property values were increasing, footpaths through backyards were being cut off, and communal wells were disappearing. Suddenly there were areas designated “working waterfront.” What does that even mean? Dworsky thought. It all used to be working waterfront.

Dworsky, who fished for 40 years and owned what he says was the slowest boat in town, photographed people whose trust he had gained over time. “The closer you get, the more you disappear,” he says. He knows the name of every person in his collection of 1,500-plus slides, now housed at Penobscot Marine Museum in Searsport. None of his images was staged.

McGuffie and his grandson head out on a glassy morning to pull traps. The epitome of independence, the old Yankee hunted and farmed, cut wood to heat his house and pulled a living from the sea.

McGuffie and his grandson head out on a glassy morning to pull traps. The epitome of independence, the old Yankee hunted and farmed, cut wood to heat his house and pulled a living from the sea.Now 63, Dworsky has an unkempt beard and bushy eyebrows that dance with his smile. He’d always been drawn to photography but never studied it formally. He remembers flipping through the pages of National Geographic as a young man, looking for insights into fill flash, depth of field and other techniques.

Dworsky’s images, taken between 1989 and 1993, captured a world where multiple generations of fishermen earned a living by going to sea in small boats, in all seasons and all weather. It was a world where community wasn’t a buzzword or a platitude, but the very fabric of life.