Operation WetVet

A former Marine helps veterans cope with PTSD one fishing trip at a time

More than 25 miles offshore, the former combat soldiers were able to relax, talk and leave land-based concerns behind for a few hours.

More than 25 miles offshore, the former combat soldiers were able to relax, talk and leave land-based concerns behind for a few hours.Patrick Orth, a Marine combat veteran and Purple Heart recipient, had never sat in a fighting chair. Few of the Marines on the 51-foot sportfisherman that day had.

But you couldn’t tell by watching him. Orth looked like a natural, sitting with knees slightly bent, leaning forward, throwing his weight back with each rhythmic pump of the rod. A vast expanse of ocean stretched in every direction.

Up came the mahi-mahi. The mate leaned over the side of the Forbes, gaffed the fish and sent it wheeling into the fishbox.

“That your first mahi?” the mate asked.

“This is my first time being on a sportfishing boat,” said Orth, a 31-year-old former Marine Corps lance corporal from Asheville, North Carolina.

Orth got up from the fighting chair and joined the other veterans, who were relaxing in the shade of the flybridge overhang. He sat on the gunwale. Someone handed him a beer. “That’s badass,” Orth said after a moment’s reflection. “You already got five stars in my book.”

Operation WetVet

From front lines to tight lines: Osvaldo “Ozzie” Martinez Jr., a 35-year-old former Marine Corps Corporal, started Operation WetVet to bond with his brothers-in-arms.

Photography by Jason Stemple

Operation WetVet

Steven Diaz, a corporal with the Regimental Combat Team-2, 1st Marine Division in Iraq, on the Charleston, South Carolina, charter boat Family Tradition, a 51-foot Forbes.

Operation WetVet

Sergeant Vernon Miller, one of seven military veterans in Charleston

for the inaugural Operation Wetvet Dolphin Smackdown.

Operation WetVet

Lance Corporal Patrick Orth gets in the fighting chair for the first time.

Operation WetVet

“The reason I chose offshore fishing over inshore and backcountry is that excitement of watching that fish jump and hearing the reel scream,” explained Martinez.

Operation WetVet

Up comes the Mahi.

Operation WetVet

Orth, the crew, and the rest of the vets look on.

Operation WetVet

“I started it to replace the nightmare of the roadside bomb with catching a sailfish,” said Martinez, or in this case, a barracuda.

Operation WetVet

“These veterans need to recognize [deep sea fishing] as a good adrenaline rush,” said Martinez. “Most of the time for us, it’s a muffler making a loud sound or somebody slamming a door. An unexpected noise, an unexpected reaction that we cause.”

Operation WetVet

“Don’t get me wrong, I think these guys deserve to be taken out fishing,” explained Martinez. “But I want veterans to get something out of it other than a T-shirt and an experience.”

Operation WetVet

Comanche Reef was teeming with amber jacks. Trips like this one are essential for “guys to build that camaraderie back,” says Diaz. “For us, that’s the biggest thing that we miss. Especially when you’ve been in combat.”

Operation WetVet

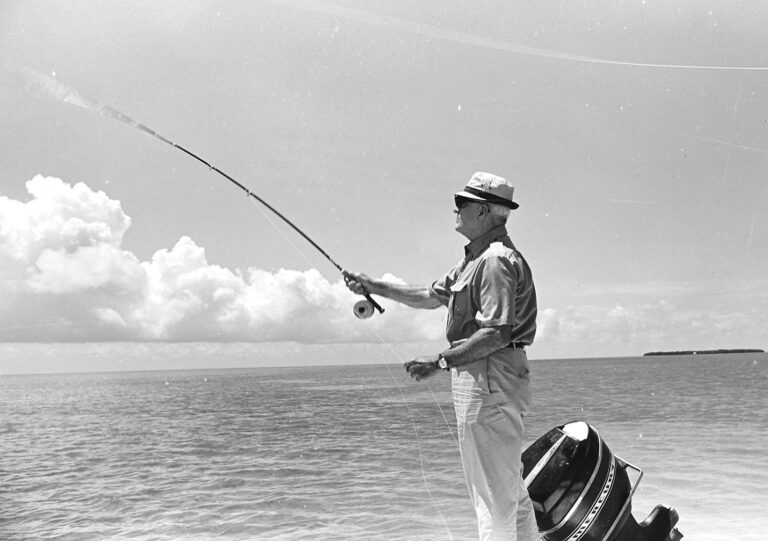

Command Sergeant Major, USA, Retired Wendell Hardwick jigs for amberjack. Says Diaz, “when you’re hanging out with us and we’re in situations like [this one] where we’re given a goal and an objective, and there’s a little bit of danger, it makes us open up.”

Operation WetVet

“I want to teach these guys how to function with their Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder,” said Martinez, “because this doesn’t go away, we’re going to live with it forever.”

Operation WetVet

Orth and Diaz unfurl the flag.

Operation WetVet

Once unfurled, it’s got to be folded properly for the return trip home.

Operation WetVet

Orth giving the flag special care.

Operation WetVet

One of the mates offers a hand.

Operation WetVet

Look for the full story on Martinez and Operation WetVet in our September issue

Positive Rush

Vernon Miller (left) and Steven Diaz with a matched pair of amberjacks.

Vernon Miller (left) and Steven Diaz with a matched pair of amberjacks.On this day eight combat veterans were getting a taste of offshore fishing while trolling on two boats along the edge of the Gulf Stream, about 60 miles southeast of Charleston, South Carolina. They’d come from there and neighboring states. All had seen combat in Afghanistan or Iraq. Many had earned Purple Hearts for being injured in the line of duty. And many, if not all, suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD.

Operation WetVet had brought them together. It’s a nonprofit organization based in Miami that former Marine Corps Cpl. Osvaldo “Ozzie” Martinez Jr. started after he returned from Iraq. The 35-year-old Martinez has struggled with PTSD for 10 years. “I started it to replace the nightmare of the roadside bomb with catching a sailfish,” he said.

On the water Martinez looks for teachable moments when he can show combat veterans that there is a difference between positive and negative adrenaline. “The reason I chose offshore fishing over inshore and backcountry is that excitement of watching that fish jump and hearing the reel scream,” Martinez said. Veterans need to learn how to recognize good adrenaline rushes; those who have been in combat overreact when they hear a loud muffler, for instance. “I want to teach these guys how to function with their PTSD,” Martinez said, “because this doesn’t go away. We’re going to live with it forever.”

In Iraq in 2004, Martinez served with the 3rd Assault Amphibian Battalion, 1st Marine Division. He got his first glimpse of the destruction of war as part of a convoy along a six-lane highway between Kuwait and Iraq. U.S. and British forces had driven there during the 2003 invasion. Smashed vehicles and blackened holes from bomb blasts remained.

“It didn’t feel real,” Martinez said. “It felt like something out of a movie set.”

The Marines in his unit called Martinez “combat camera” because of the digital Nikon he carried. He saved some of the photos, each one time-stamped and dated. One captured a 23-year-old Martinez outside Camp Fallujah. Another shows him sitting next to a smiling Marine at base camp, where they watched episodes of The Sopranos and any movies they could get on DVD. With the whitewashed brick walls behind them, the setting could easily be mistaken for a college dorm room.

“This guy right here, Puckett,” Martinez said, “he died less than a month after that picture was taken. That’s his last living picture.”

Martinez sometimes can’t be out at a restaurant or some other public place without jumping at the sound of a door slamming. But out on the water he feels different, and he wants to help other veterans feel that way, too.

The WetVet organization helps veterans recognize positive adrenaline rushes, such as the howl of a reel when a big fish makes for the horizon.

The WetVet organization helps veterans recognize positive adrenaline rushes, such as the howl of a reel when a big fish makes for the horizon.Camaraderie

The day Orth caught his first mahi started about 4:30 a.m., when the sun was barely above the horizon. The charter boats Family Tradition and Little Less Talkingcruised out of Ripley Light Yacht Club with Steven Diaz in a helm chair on one of the flybridges. In Iraq, Diaz was a corporal in a Marine platoon assigned to convoy security. He’d been searching for and clearing homemade bombs — improvised explosive devices, or IEDs in military jargon — when one exploded under his Humvee. The blast left him blind in one eye.

On the boat, Diaz appeared to be enjoying himself. He and Orth unfurled an American flag in the cockpit. The others traded good-natured ribbing, laughed and told war stories. The sense of camaraderie on the boat, they said, was similar to what they experienced in the service.

“For us, that’s the biggest thing that we miss, especially when you’ve been in combat,” Diaz said. “When we’re in situations like [this one], where we’re given a goal and an objective, and there’s a little bit of danger, it makes us open up.”

For Orth, the day brought back memories of growing up, fishing for largemouth bass with his father. “For a lot of my free time, when I got home from Iraq, I was in the river fishing,” Orth said. “Fishing does help out a lot. It takes your mind off stuff that you got problems with.”

Sgt. Vernon Miller, a tall, quiet 31-year-old former infantry machine gunner from Greenville, South Carolina, seemed introverted and reserved on the boat, as if he were straddling two worlds. He was retired from the Special Forces. The week after the fishing trip, he was scheduled to have the nerve endings on the right side of his back cauterized to help manage his back pain, a nagging injury he sustained over three deployments. He gazed at the horizon and didn’t say much.

In the morning, the boat trolled for mahi, and the action was slow. By late morning, only two of the vets had hooked fish, so the boats moved inshore to a reef and jigged for amberjack.

The men relaxed and talked and laughed. Each took a turn in the chair. Some 25 miles offshore, there was order, a system. They could leave their land-based concerns behind, at least for a few hours.

Fishing has a way of keeping you focused on the here and now, as former Marine Cpl. Steven Diaz discovered on an offshore trip.

Fishing has a way of keeping you focused on the here and now, as former Marine Cpl. Steven Diaz discovered on an offshore trip.Struggles

After returning home in 2006 from two tours in Iraq, Martinez suffered from depression. His company had taken the most casualties out of his battalion, and he says he had survivor’s guilt. He put on weight. He was living fast, partying. But he didn’t understand the extent of his PTSD until two years later, when the Marines reactivated him. He was on a plane bound for Kansas City, Missouri, when he learned that in one month he would be deployed to Afghanistan to train Afghan soldiers.

“I started having anxiety attacks and nightmares because now I was no longer repressing it,” Martinez said.

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs gave Martinez a PTSD rating of 70 percent. (A rating of zero percent means PTSD has not affected a veteran’s ability to work, while a 100 percent rating indicates total incapacity to work.) Shortly afterward, he received a letter stating that he no longer met the physical and mental requirements of the Marines. He was “non-deployable.”

The nightmares and anxiety attacks persisted. He self-medicated with alcohol. He was prescribed psychotropic drugs. Neither worked.

Martinez would drink himself into a stupor and pore over the more than 3,000 pictures he’d taken in Iraq, ruminating about the friends he had lost. Unable to relate to his friends and family in Miami, he withdrew. His wife kicked him out. His son had just been born, but Martinez still had trouble finding joy in life. He moved in with his grandfather and shut down, barely interacting with the outside world.

The veterans jigging for amberjack

Feeling the camaraderie while folding the flag

The bites kept coming

Steven Diaz with a barracuda

Heading out to the fishing grounds at first light.

Sea Change

On a camping trip in 2014 with former platoon mates in California, Martinez received news that a friend had committed suicide. He realized that many of his comrades were having the same struggles, or worse, with PTSD that he was. Shortly after that, a friend in Miami invited Martinez out lobstering. Being on the water changed things. Martinez believed he could make a difference if he could combine the camaraderie he’d felt camping with the exhilaration of offshore fishing.

He organized the first fishing trip out of Key Largo, Florida, with 20 veterans. Next, he asked counselors from the Miami Vet Center to join the fishing trips. Being anglers themselves, they were only too happy to help, Martinez said.

Former Marine and organization founder Ozzie Martinez hoists a mahi.

Former Marine and organization founder Ozzie Martinez hoists a mahi.Starting Operation WetVet gave Martinez a purpose. Helping combat veterans deal with PTSD, he said, helped him come to terms with his own issues. Martinez started seeing a therapist. He and his wife reconciled. He is now the father of two boys.

Through the generosity of captains willing to donate charters, Martinez hopes to broaden the scope of Operation WetVet to reach more veterans in more coastal communities.

“A lot of these guys are in dark places similar to my own,” Martinez said, citing statistics that suggest as many as 22 veterans a day commit suicide. “Whatever the figure is, there are veterans committing suicide every day due to PTSD. I’m not trying to just get these guys fishing. Everyone I’ve taken out on these trips, I’m still in contact with. They have my personal number. I’m letting these guys know that they’re not alone.”

It was late afternoon when the boats returned to the docks, where a group had assembled. One of the charter captains thanked the veterans for their service. Others echoed his sentiments. A large American flag billowed in the breeze.

Vernon Miller, the quiet Special Forces veteran, left without saying much. A couple of days later, though, he explained in a text how, sometimes, he would attend group therapy. He rarely said anything there, but he said those sessions and outings such as the fishing trip were helping.

“Events like this let you know you’re not alone and link you up with brothers in the same shoes, who you can reach out to and they can reach out to you,” Miller said. “It’s just a reminder you’re not alone, and that’s the most important thing for guys to realize. At least it was for me, and still is today.”

For information on Operation WetVet, visit operationwetvet.org or call (305) 812-2429.