As we run south, away from the launch ramp at C.S. Lee Park in Geneva, Florida, the narrow ribbon of dark water begins to burst open into a massive floodplain. My eyes adjust to the vast, wide-angle landscape as I slowly turn my head, letting my mind create a panoramic image of the mosaic. Tall grass swaying in the breeze as far as I can see. Hammocks of sabal palms and cypress trees drooping with Spanish moss provide the only dots of shade in an exposed vista.

When you live on a pancake, as I do in central Florida, you must go to the beach or look inland to find an expanse of wild country such as the one unfolding in front of me on the St. Johns, the state’s longest river. Otherwise, the horizon is typically busted up by another new Walgreens that somehow sprouted up overnight like a daylily. Not here. Not on the oasis that is the St. Johns.

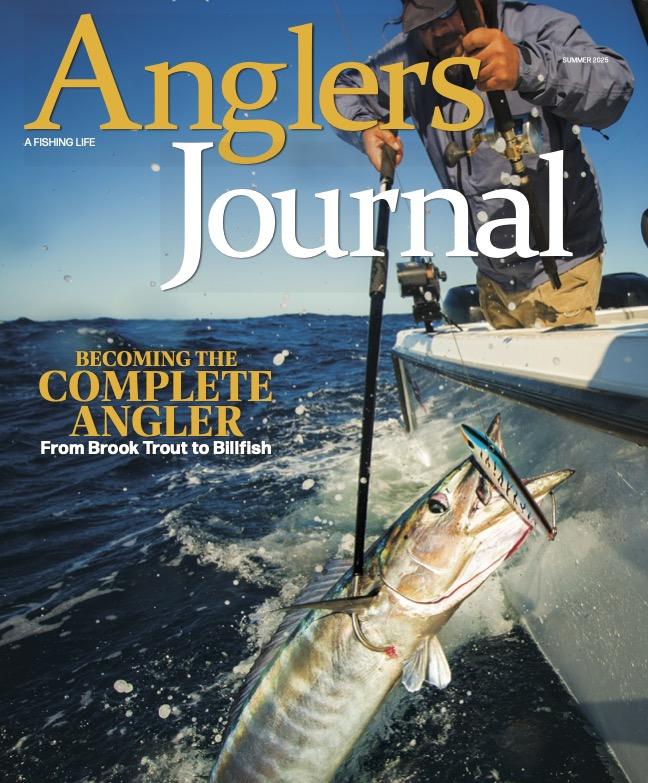

For decades, Jon Cave has explored the vast floodplains of Florida’s longest river, the St. Johns.Ian Sasso

For decades, Jon Cave has explored the vast floodplains of Florida’s longest river, the St. Johns.Ian SassoI was sitting in the bow of Jon Cave’s aluminum jonboat, powered by a 15-hp Mercury outboard, as we carved our way through a meandering stretch of water. Cave is a former guide who lives near this section of the river. These days he is an in-demand fly-casting instructor, and his mind is almost always debating some nuance related to his favorite pursuit.

“I don’t know if it’s even healthy, but I have kind of a one-track mind in that I mostly think about fly-fishing,” Cave says with a laugh. “I don’t have a lot of outside interests. I like to paint, but I paint fish. I like to take photographs, but they’re all fish. My circle of friends are all fly anglers, but that commonality makes for a great friendship.”

While Cave, who is in his early 70s, is a fly-fishing purist, he is by no means a snob. He grew up in Indiana when fly-fishing wasn’t nearly as popular as it is today. As a boy, he’d go to the Western Auto store to look at fly gear and dream about fishing smallmouth streams. His eyes were opened when he met guide and tournament caster Ed Mueller.

“He could be cantankerous, but because I loved fly-fishing, he took me under his wing a little bit,” Cave says. “I’d buy him breakfast on Sundays, and he’d teach me. I loved it. I always loved it, and I wanted to get really good.”

“There’s something beautiful about fitting into the environment,” says Jon Cave.Charlie Levine

“There’s something beautiful about fitting into the environment,” says Jon Cave.Charlie LevineSitting in Cave’s boat, I feel like a younger version of the man driving. Every time I’m with him, he teaches me a useful technique. Joining us is Ian Sasso, a filmmaker and another one of Cave’s students. Sasso took Cave’s class when he was 15 and fell hard into fly-fishing. Cave told the teenager he could come over any time he wanted. Now 34, Sasso took advantage of the offer. “I couldn’t keep him away. He was a like a fly-fishing pest,” Cave jokes. “He was eager, and I like that.”

Cave and his younger brother Paul are both Florida fly fanatics. They fell in love with the state’s fishery as kids, visiting their grandparents every summer at their home in Naples. Paul is still guiding. “I knew when I was very young that I was going to move to Florida,” Cave says. “We’d fish on Marco Beach, and there was nothing there. I just fell in love with it.”

Cave cut his teeth on saltwater fly-fishing in the early 1970s, and when he started guiding, he strictly fished the salt but often found himself stopping at the St. Johns River on his way back from the coast. He’d catch a few bass and flush the engine on his boat with river water. “I still consider myself primarily a saltwater fly-fisher, but I also consider myself an all-around fly-fisher,” he says. “That was always my goal. I feel as comfortable on a trout stream as I do on a bass river or the flats.”

Cave, who worked as a guide for more than 20 years, holds a degree in natural resources, specializing in fishery and water issues. He also worked as a general contractor at times to pay the bills, but all of that took a back seat to fly-fishing. As he built his guiding business, Cave started to write articles, and he’d often take assignments to discover new fisheries in underdeveloped places, such as Honduras. But he always found himself back on the St. Johns, steering around oxbows and casting to bass. “Fishing here is as good as there is,” he says. “We have a tendency to overlook our own backyard, but if you’re willing to put in the time and look around, it’s right here.”

Shad begin to show up on the St. Johns River in the beginning months of the year. For anglers, the shad are the first course and largemouth bass are the main dish.Charlie Levine

Shad begin to show up on the St. Johns River in the beginning months of the year. For anglers, the shad are the first course and largemouth bass are the main dish.Charlie LevineThe seasons in Florida tend to meld together with few demarcations, such as changing leaves or the arrival of tulips, to close one season and begin the next. Seasonal changes are subtle on land but evident on the water. As water temps change, new species of fish arrive, signaling a seasonal shift.

For anglers on the St. Johns, winter means waiting for shad to appear. The shad swim thousands of miles from as far north as the Bay of Fundy in the Canadian Maritimes to return to their natal waters to spawn. The first shad show up on the St. Johns around the end of January and stay for a couple of months, until the switch flips and they head back to sea. For Cave, shad are the appetizer; bass are the main course. “Bass, especially Florida black bass, are one of my favorite fish to catch on a fly,” he says.

The water is high on this late-January afternoon, and Cave wants to head upriver, which means running south. The St. Johns is one of the few rivers in North America that flows north. It runs for 310 miles, from Fort Drum Marsh west of Vero Beach to Jacksonville. With little drop in elevation, the river current moves like molasses, about 0.3 mph, roughly the walking speed of a gopher tortoise.

The arrival of pelicans indicates that fish are not far behind.Charlie Levine

The arrival of pelicans indicates that fish are not far behind.Charlie LevineCave takes us to some of his favorite spots, where we beach the boat, walk the banks and cast. He is not a fan of crowds or the recently upgraded ramp for larger boats. With more boats on the river, he is careful about sharing his spots.

I find myself transfixed on the views and wildlife. I spot a kingfisher zipping above the grass while gators linger along the shore like lazy hippos. We see some anglers in waders fishing from a bank. “Tourists,” Cave says. “Locals don’t wear waders — they wet-wade.”

The St. Johns is a broad river full of shallow bowls and more than a dozen large lakes. The Seminole-Creek people call it Welaka, the “river of lakes.” Depths vary from ankle-deep to a few feet overhead. It’s a dark, blackwater river stained from rotting vegetation and dead leaves that leach tannins. During summer, the water levels drop, and bigger boats can’t get into Cave’s most treasured spots.

As we slow down, a 7-foot gator lying on a half-sunken tree lifts its head and eyes us. We beach the boat a few-hundred yards downriver, grab our fly rods and step out. I use the butt of my rod to poke at the tall grass as I stomp, hoping to scare off any water moccasins or small gators that may be underfoot. Cave points to spots and shares stories as we fish. “Right here, I tied on a little Clouser and caught 30 bass,” he says.

Anglers walk sections of the St. Johns River and fish it much like a trout stream.Charlie Levine

Anglers walk sections of the St. Johns River and fish it much like a trout stream.Charlie LevineWe walk the banks like we’re fishing a trout stream. Cave steps along barefoot, but I wear calf-high, waterproof deck boots. The river is full of little creek mouths, some of which were cattle trails that formed into small riverlets. Cave says they are “ecosystems of their own.” Nutrients run down the patted grass and mud before draining into the river. Those nutrients draw in the bait, which catches the eye of predators.

Bass here will eat anything from minnows to dragonflies. “Whatever’s out there, they’re going to eat it,” Cave says, but they can be finicky at times. “I’ve seen them get real picky when they’re keyed in on one thing only.” Cave enjoys the challenge of figuring out what that one food source may be and finding the perfect fly to imitate it.

We fish poppers along fallen timber and palms. I get hung up repeatedly. I’m embarrassed, but Cave is cool about it. He takes my rod and shows me a trick, snapping a quick roll cast to pop the fly off the backside of a log.

Cave is tall, and I enjoy watching him cast. He doesn’t seem to put much effort into it, yet his casts sail 10 feet past mine and unroll gracefully with quiet drops. Between my parade of expletives, he gives me pointers as I cast. “Tuck your elbow in a bit,” he says, and laughs when I apologize for hanging up on a limb. “It happens all the time out here.” Somehow I don’t lose a single fly.

While shad are often plentiful in the winter months, they can be tough to hook.Charlie Levine

While shad are often plentiful in the winter months, they can be tough to hook.Charlie LevineThe bass are not playing along, so we run farther south to Puzzle Lake to fish a spot where Cave caught a big sunshine bass last year. These are hybrids created by mixing female white bass with male striped bass. As we enter the lake, the water widens but is super shallow, and there’s only one marker, a leaning white section of PVC pipe that seems to have been haphazardly placed in the middle of nowhere. When water levels drop, it’s easier to find the river channel, but I have no idea where it is as Cave steers. He slows down as the water gets skinnier by the minute. A massive flock of white pelicans sits along an edge of tall grass, a sure sign that shad aren’t far away.

Cave cuts the engine and uses a wooden closet rod to pole the boat. “I pride myself on the fact that this boat is simple,” he says. There’s no GPS and no trolling motor. As he poles, he calls himself “Jon Kota,” referring to a Minn Kota trolling motor. He also uses a long paddle while standing. “I like doing stuff myself,” he says. “There’s something beautiful about fitting into the environment, and I get that feeling with a paddle in my hand.”

As the sun begins to dip lower in the sky, we work our way back toward the ramp and find a sizable school of shad cutting, or “washing,” across the surface. These fish are not here to eat; they have something else in mind. The fish are mating. The underside of a shad is sharp, almost like a serrated knife, and the shad cut each other as they do their dance.

Largemouth bass are premier gamefish on the St. Johns River.Ian Sasso

Largemouth bass are premier gamefish on the St. Johns River.Ian SassoWhen Cave was guiding, catching 25 shad a day was the common high-water mark. While he says he has had enough of shad fishing, these fish are proving hard to hook, and I can see Cave savoring the challenge of figuring out what combination of line and fly will work best.

Cave carries a mix of flies that he has tied, including patterns he developed more than 30 years ago. The shad fly he ties on has a big head, and Cave attaches it to a sinking streamer line to get it down in the water column. He tells me to use a floating line and a heavy fly so we can determine the depth at which the fish are biting. I watch Cave vary his retrieve speeds until he comes tight to a decent shad that thinks it’s a tarpon and leaps out of the water. Cave is smiling. “They want a slow retrieve,” he says. “Almost still.”

— Subscribe to the Anglers Journal Newsletter —

We fish till dusk turns to dark, then stop at another creek mouth not far from the ramp. Fish cut and jump across the surface around the boat, but they’re still playing hard to catch. I manage to hook one on a Clouser. Cave fishes a smaller fly. I like how the shad jump and dig as they fight. They’re fun to catch, but they’re no bass. The appetizer has been served, but we’ll have to come back later in the year for the main course.

I stare at the last remnants of the sunset and soak in the setting. The open grasslands look more like the Serengeti than a swath of floodplain sandwiched between the population centers of Orlando and Florida’s east coast. This section of the St. Johns has not changed much in hundreds of years. The shad were here then, just as they are now. It’s a last great place in a state under perpetual development.

“The river cuts through the noise — the real world versus the synthetic world,” Cave says. “The St. Johns is a treasure to this country. It’s no different than the Yellowstone or any of the great fishing rivers.”