“How many of those do you smoke a day?” ask incredulous clients of Capt. Frank Crescitelli regarding his prodigious intake of La Flor Dominicana Double Ligero 700 maduros. “That’s a proprietary number,” is his canned response. But if there’s anything that precedes Crescitelli more than the oversized cigars that seem eternally perched in the corner of his mouth, it is his superlative mastery of any and all manner of saltwater fishing.

Granted his accolades, the man deflects praise with utmost grace. “I gravitate toward the things I suck at,” the auto mechanic-turned-fishing guide tells photographer Tom Lynch and me as we slide out into a section of channel Crescitelli calls “The Hole.” His right-hand fishing partner, a 10-year-old spaniel named Mia, giddily pitter-patters back and forth across his 24-foot Bluewave bayboat. His favorite spot on Little Egg Harbor is conveniently situated directly behind his canal-side, Long Beach Island, New Jersey, home.

Conjuring how Staten Island-born Crescitelli, who is 61, helped put New York City on the map for both recreational fishing and fly-fishing presents a puzzling dichotomy. Juxtaposing the larger-than-life, mustached, cigar-chomping, falsetto-cackling, television-show-hosting, tournament-founding, world-record-hounding fiend who at the same time bears the meticulous studiousness of a fly-fishing devotee is, in a word, a stretch.

But then Crescitelli, or Captain Frank, as he is known to his clients and the greater fishing community, is full of dualities. It is often joked that any charter captain who can manage to stay afloat was surely born with a silver spoon. Although there are plenty of exceptions, Crescitelli is surely among the most storybook tales of them all. Spend even five minutes in conversation with the man behind Fin Chaser Charters, which may be New York City’s most renowned light-tackle service, and you quickly learn his dedication to his passion — or addiction, as he refers to his calling.

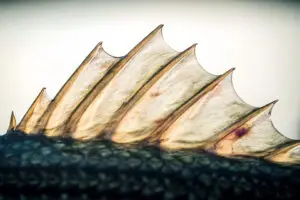

We are after weakfish, gray trout, “bastard trout” or squeteague, as the Lenape people called them in Algonquin. Cynoscion regalis, by their scientific Latin name, are an enigmatic, cyclically present, vampire-fanged member of the drum family found between Nova Scotia and Florida along the Eastern Seaboard.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration deems weakfish “endangered,” perhaps in part because, as Crescitelli says, “we know so goddamned little about them.” Being of only moderate economic importance, not much research goes into the weakfish’s life cycle or anatomy, but they do seem to come and go in waves — every 10, 12 or 14 years.

It might be this uncertainty that appeals most to Crescitelli. That, and the fact that a large specimen was one of his first big feats in fishing. He says that “maybe 6-pound” fish, at the time of its capture almost half a century ago, won him summer-long neighborhood acclaim among his fishing cohorts in the Staten Island neighborhood of his adolescence, Ocean Breeze. When landed beneath the Verrazzano Bridge, it was called a 10-pounder.

The telltale signs of a fishing addiction presented in Captain Frank early on, and he minces no words on the matter. “I’m a maniac. Thank God for my wife, Sharon. She’s the pragmatic one,” he tells us, as he’s on his third fishing outing of the day, having been seeking out grass shrimp in hopes of stockpiling chum so we might entice a better nighttime bite. “That’s how you know you have a problem, honestly,” he says. He’s been playing this proverbial slot machine rather unsuccessfully for more than a week ahead of our planned outing, and he’s doing his best to manage expectations like a good guide — and a jaded addict.

“Fishing saved my life, because most of those kids from that neighborhood certainly didn’t continue to fish,” he told me over the phone while we were fine-tuning plans for a late-spring weakfish outing. “A lot of them had other problems in life,” he added, offering up a few anecdotes. “My best friend, who wasn’t a fisherman, had a heroin problem, died of an overdose at probably 40. Another kid, an alcoholic, another kid, just a wreck of a life. The only kids who I knew I could see had some sort of successful life or regular life were sports kids. And I sucked at sports. But there were a few kids that were into fishing because we had a focus. We’d stay out all night partying, but I had to go fishing. So I stopped before the sun came up and went home and got my fishing gear and then went fishing.” Salvation comes in many forms.

I first met and fished with Crescitelli a few years ago, during an arthritically damp, early-spring storm, which oscillated between driving sleet and snow but produced an early-season bite with far too many striped bass to count in the backwaters of Raritan Bay. It was one of those first, brief but productive pushes of fish that remind you how fleeting a fishery can be. Here today, gone tomorrow.

Those are precisely the sorts of odds Crescitelli thrives on. A gearhead and a mechanic by his original trade, the man loves a good problem to solve. It seemed that with each creek, drop-off, rip and boulder field fruitlessly probed, his stogie-studded smile grew wider, and with every joke and wisecrack, his guffawing grew louder and more emphatic. By the time we connected with and boated our first fish, which Crescitelli located on a 2½-foot mud flat, fingers, toes, lips and spirits were well beyond numb. I, twice his junior, was stiff as a board. Crescitelli was clearly running some inner furnace that I’ve yet to discover in myself.

In these days of Yelp and open-source customer and client reviews on the web, testimonials are as double-edged a sword as any, but one that Crescitelli takes deep pride in comes from a long-standing client: “The only problem with Captain Frank being your guide is you don’t know who’s having more fun on the trip, you or him, but you’re the one paying.” Fish or no fish, you might find yourself forgetting why you’re out there altogether with Crescitelli. That, to many, comes as a welcome departure from our daily lives, particularly to those of us tethered to the hustle and bustle of a metropolis like New York City.

Life on the Line

The third of four children raised by a single mother on welfare, Crescitelli knows something about foolish appetites. He grew up fishing the Naughton Avenue Jetty, as much as weather and timing permitted. It lent him a drive, a work ethic and a romanticism toward the sea, a respite from the hardscrabble socioeconomic existence ashore, where hardships were certain and prospects were few. Not that the fish weren’t, too. “In those days, the fishing sucked,” Crescitelli says, but the barrier to entry was low. With a $20 Zebco surfcasting setup and a handful of lures, a kid on a jetty could afford to dream. At least in ways that he couldn’t or felt he shouldn’t ashore.

As Crescitelli came of age to work, his tackle collection expanded to the point that, in his late 20s, he acquired a fly rod, which in 1980s and ’90s Staten Island was about as far-fetched — not to mention being reputationally endangering — as an angler could be. But it made him a renaissance angler, and ultimately led to a career few in those parts had ever conjured.

That fly rod paid off in ways neither Crescitelli nor anyone else would have ever predicted. He became the only Orvis-endorsed saltwater fly-fishing guide in the Staten Island area, and soon, a cash-flush Wall Street clientele came calling. “I’d pick them up in Manhattan at 4:30 after closing bell, and we’d fish till after dark,” he says. Word of mouth was exceptionally strong in those days, and before he knew it, he had a full calendar of deep-pocketed anglers.

Not that Crescitelli ever lost his sense of community, his upbringing, or what I can only identify as his innately upstanding nature. Working his way aboard multiple boats, he wouldn’t shy away from soaking baits, less ambitious bottom-fishing outings with novice anglers and trolling when it came down to it.

He also found his way into chasing school-sized bluefin tuna off the New York Bight at a time when the idea was nearly unthinkable. He got into tournament fishing, favoring prestigious — and hefty-purse — events targeting punky, acrobatic white marlin most of all. The competitive streak is a big driver for Crescitelli. He’s always after a world record on the fly within what seem to me to be impossible tippet classes, particularly 6-pound-test endeavors for yellowfin tuna and cobia. He managed to hold a 20-pound tippet record for weakfish for all of a day before a friend caught a bigger one. His buddy was reluctant to submit the fish to the IGFA, so Crescitelli forced him to, sabotaging his own standing.

The Manhattan Cup, an annual New York Harbor-based charity tournament for striped bass and bluefish that Captain Frank founded, hosts and organizes — with co-director Gary Caputi, among a cast of others — is in its 23rd year honoring and benefiting veterans. It is a herculean production that takes place in early June with the goal of hosting at least 22 veterans to raise awareness of the haunting statistic that an average of 22 veterans succumb to the traumas of military service each day by taking their own lives.

Rooted in the Big Apple

Crescitelli was running a charter near the entrance to Jamaica Bay on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, when he noticed a plume of smoke coming from one of the twin towers at the World Trade Center. His wife called and told him that a plane had struck the tower, as he and his client watched in confusion.

They decided to get a closer look, and as they approached lower Manhattan, a second plane flying precariously low turned and veered into the other tower. He and his client met with a U.S. Marshall who instructed them to prevent traffic from exiting a Jersey City marina on the New Jersey side of the Hudson River. Following orders, they remained there for hours without a radio or any information of what transpired that day.

In addition to the trauma of the events they witnessed, Sharon and Frank lost a family member and realized that living in New York City would become untenable. For a time afterward, even fishing was laced with unthinkable hurdles. They settled on a house in the waterside community of Beach Haven on Long Beach Island, New Jersey, where they’ve been since 2002. The fishing, Crescitelli concedes, is less than stellar, but boat traffic is low.

Tonight, we have unfavorable conditions thanks to too much rain and an incursion of “slime weed,” which makes fishing close to impossible. “We did better than I thought we would,” Crescitelli summarizes as we conclude our trip, which has produced a mixed bag of “exotics.” Cownose rays and what we all agree might contend for a world-record smooth dogfish are about all that grace our hooks, apart from a handful of small bluefish, short fluke and snagged horseshoe crabs, whose mating rituals we disgracelessly (and regretfully) interrupt.

No matter the stakes, there’s an element of gambling to fishing. Esteem is relative to the conditions at hand, and Crescitelli isn’t above or below whatever comes his way. To wit, not one among the three of us is a stranger to being skunked. Still, thanks to a pop of color at sunset on an otherwise dull and drab day, we manage to find aesthetics in the midst of our outing.

Crescitelli isn’t slowing down, but he ponders his future. “When I stop being jazzed about it,” he says, “it’s time to hang it up.” Citing that fishing is in a downturn, particularly on the striped-bass front, he doesn’t fancy the prospects of fishing with chunks of bunker or trolling to put clients on fish steadily and predictably enough.

Crescitelli is zeroing in on the things he loves. “I don’t feel old in my brain — my body, different story,” he says. “I’m going to be 62 in November. You’re counting down at that point. You’re not counting up. I always talk about when my kids were young. I’d be like, OK, once they’re in school, then we’ll have more free time to do this. You’re always counting up, looking forward, and then your kids go to college, get married. …

“And then you look at your age and talk about what you want to do with the rest of your days,” he adds. “I don’t know any 72-year-olds that go 100 miles offshore to the canyon in a center console. So maybe I got 10 canyon seasons where I can go on my own boat? I can go with people in bigger boats, and I do fish tournaments on a big boat. I’m fortunate to do that, but it’s not the same as your own boat.”

Crescitelli stops himself. “I was riding on a friend’s Spencer recently, and he asked me to drive. I tell him, ‘This? This isn’t driving, this is sitting and watching,’ ” he says of operating a big sportfish from the flybridge. “Next thing I know, he’s bringing me an ice pop. I had to take a selfie of myself with that.”

Some of us don’t, can’t, won’t ever grow up.

He’s not about to put his canyon-running 35-foot Contender to bed, but I foresee a sportfisherman of his own in the coming decade — boxes of La Flor Dominicanas, freezer full of ice pops — and not a gripe in the world from Crescitelli who, when fishing, is nothing more and nothing less than a kid in a candy shop.